In this post, we share our work at the intersection of machine learning and security. We look at secure device pairing, a task in which we are trying to establish a secure connection between two devices wirelessly. We establish a protocol in which the devices can be paired securely if each device can recognize a melody played by the other. To enable this application, we build a machine learning system that can perform melody recognition.

We begin this post with a focus on the security application: describing the secure device pairing problem, highlighting drawbacks of existing solutions, and finally demonstrating how an audio-based pairing approach can be used to overcome them. In the second half of the post, we focus on the machine learning task of melody recognition: sharing our experience exploring different approaches to the task, and detailing a solution that performs well even in noisy environments.

Listen to the melody below, which consists of 8-notes played in sequence (in a noisy environment) – can you identify any of them? The system we build later in the post gets them all right.

Secure Device Pairing

Most of us have used Bluetooth at some point in our lives. We are familiar with the routine of “pairing” two devices, like a phone and car, which finishes with entering a PIN or comparing some numbers. The goal of this last step, of course, is security. You don’t want someone next to you to be able to eavesdrop on you or trick you into connecting to them to steal your data. However this security step is often annoying (typing a PIN) or easily skippable (comparing numbers). This problem promises to become increasingly common as new applications like smart cars and connected homes continue linking things in the physical world together.

We set out to create a better way of securing device pairing in the physical world. Instead of typing a PIN or comparing numbers, a simple audio melody is played and automatically recognized. An attacker would only be able to subvert the pairing by playing their own melody, which would be easily noticed. Otherwise we do not need to do anything.

So how does this work? How can entering a PIN, comparing numbers, or recognizing an audio sequence make things secure? Let’s first learn about secure device pairing in general, before delving into the details of how we use audio to improve the process.

Background

Like many secure communication discussions, we start with our characters Alice and Bob. In this case, Alice has a device she would like to pair with a device of Bob’s that she hasn’t connected to before. At the end of the pairing, the goal is for Alice’s device and Bob’s device to share a secret key that only they know, even if there are attackers who listen or interfere. The devices would then be securely paired because they can use the secret key to encrypt all of their communication so that no one else will be able to eavesdrop on or tamper with them.

There are two types of attackers that Alice and Bob need to be concerned with: a passive attacker we’ll call Eve and an active attacker Mallory. Eve, as a passive attacker, can only eavesdrop on, not tamper with the communication nor send messages herself. If Alice and Bob only need to defend against Eve, they can use the Diffie-Hellman protocol to safely create a shared secret key. The challenge is when Mallory, an active attacker, is involved. While Mallory can’t subvert the Diffie-Hellman key exchange directly, Mallory can insert herself between Alice’s device and Bob’s device, tricking Alice’s device and Bob’s device into separately pairing with Mallory’s device. Both Alice and Bob will now think they share a secret key with each other, while in reality Alice and Mallory share one key, while Bob and Mallory share a different key. This allows Mallory to eavesdrop on or impersonate Alice and Bob.

To prevent Mallory’s attack, we need to add some way for Alice and Bob to be sure they are connecting to each other, not an attacker, for the Diffie-Hellman key exchange. There are several ways to do this using a third party that Alice and Bob both trust to verify each other’s identity. However, for devices and protocols like Bluetooth, finding a single third party everyone will trust is impractical. This is where Short Authenticated Strings can help.

Short Authenticated Strings (SAS)

A short authenticated string uses the idea that certain channels are naturally “authenticated” even if they are not secret. This means we know we are communicating with another party because an attacker can’t tamper with messages across this channel or will be detected if they do. For example, if Alice and Bob have a face to face conversation, they know they are communicating to the right person and could tell (and ignore) if Mallory tried to shout a different message at them. Even over the phone, Alice and Bob might be able to recognize each other’s voice, so they can “authenticate” information exchanged during the conversation.

Going back to the Bluetooth pairing example at the beginning, entering a PIN and comparing numbers also form authenticated channels. Alice sees the PIN on Bob’s device and types it into her device or compares it with a PIN on her device; an attacker presumably cannot tamper with Alice’s vision, so these channels allow short strings like the PIN to be authenticated.

Once we have an authenticated channel, we can use it to authenticate Alice and Bob’s Diffie-Hellman key exchange. All they need to do is ensure that they have agreed on the same key, since Mallory’s attacks will cause them to have different keys. One way to do this is by sending a hash, or summary, of the key over the authenticated channel. However, the hash in this case is too long for this to be practical; no one will compare or type 100 characters just to pair their phone with a car or computer. We need short authenticated strings, and it turns out there is a protocol that lets us authenticate a message using much shorter authenticated strings.

Secure Audio Pairing

However typing a PIN or comparing numbers still require a lot of active human intervention. Instead, we can use audio as a authenticated channel and automate the process. If we encode the short authenticated string as melodic notes, Alice’s device can simply the play the sound and Bob’s device can recognize it. If an attacker tries to interfere with the audio channel, Alice or Bob will hear it, so the audio channel is naturally authenticated.

Putting the steps together, two users can pair devices securely by doing a standard key exchange over a normal communications channel like Bluetooth, then authenticate the shared key for the connection with a Short Authenticated String protocol. The Short Authenticated String protocol involves each device playing a short audio sequence, which the other device must recognize. No intervention beyond passively listening is required by the users, as the only attack they need to detect is if they hear a third unexpected device playing audio. From the user’s perspective, this is an easy and seamless process.

Exploring Approaches to Melody Recognition

A key part of the secure audio pairing system is recognizing the audio notes played, which can be a challenging task in noisy environments. We use machine learning for melody recognition. To recognize a melody is to recognize the sequence of notes that constitute it. We seek to develop a system which can listen to an audio file and recognize the melody. An example recognition of a four-note melody is $[A, C, E, G]$. If we have sheet music for an audio file, we know exactly when each note is played, and for how long. In this case, the input audio and labellings are said to have alignment, and the data is said to be strongly labelled. The harder case is when we have the sequence of notes that constitute the melody, but no information on when each note is played. In this case, input data and labellings are said to have unknown alignment, the data is said to be weakly labelled, and the task is called temporal classification. We often encounter temporal classification in speech recognition, where we may know from an audio recognition that a person says “hello world”, but we don’t know the precise moments when each of the words (or phonemes/graphemes) is uttered.

Without Alignment Information

When the alignment between audio data and melodies is not given, a model must map an input sequence of audio data to an output sequence of discrete notes that constitute the melody – a temporal classification task.

In the early 2000s, graphical models such as Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) and Conditional Random Fields (CRFs) were the reigning kings for temporal classification. At that time, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), although able to provide a powerful mechanism for time series modelling, were not directly applicable to temporal classification. RNNs had an API constraint: they required target outputs for each point in the training sequence. Temporal classification with a single neural network was a feat yet unachieved.

In 2006, Alex Graves et al. introduced Connectionist Temporal Classification (CTC), a way to label sequence data with neural networks without need for either alignment data or post-processing. CTC (also called CTC-RNN to make clear that the choice of network is recurrent) defines a differentiable loss function that calculates the probability of a melody conditioned on the input as a sum over all possible alignments of the audio input with the notes in the melody. The CTC network has since evolved, and is used in state-of-the-art speech recognitions systems (see DeepSpeech2) today.

With Alignment Information

One simple way to use alignment information between audio and notes is to split the audio data into segments such that each audio segment corresponds to one output class (note). A model can then learn to map from an audio segment to a single note, as opposed to a sequence of notes. Rather than recognize the melody all at once from the entire audio sequence, we can thus recognize each note that constitutes it one audio-segment at a time. This idea is more generally called the sliding window approach, is commonly used in pedestrian detection and photo OCR (see Coursera video by Andrew Ng on sliding windows.

A major drawback of having models work on segments, rather than on the entire sequence is that context information is lost. Just as certain sequences of words make much more sense than others in accordance with the rules of syntax and grammar, certain sequences of notes are more likely than others in terms of musicality. Any model that operates at the level of segments (or words) rather than melodies (or sentences) signs off any benefit that it may have acquired from context. A popular workaround is to hybridize segment-level models, responsible for making local predictions, with HMMs, responsible for modelling global behaviors of data.

Models can also learn to recognize the entire melody from the audio sequence without any segmentations. In recent years, working with sequential inputs and outputs for neural networks has become extraordinarily effective, and has led to the popularization of the sequence-to-sequence learning paradigm.

A System for Melody Recognition

While the CTC / sequence-to-sequence class of approaches to the problem of melody recognition seemed promising, their implementations (at time of writing) were hard to get to work well. Nevertheless, this still seems a promising direction for future work, given their results in speech recognition.

We turn instead to the pre-CTC era approach of sliding windows, where a model detects individual notes in an audio segment (window) that slides through the audio sequence; the notes outputted are then preprocessed to get the melody. We’ll see that sliding windows can work incredibly well with the right choice of segment-level model.

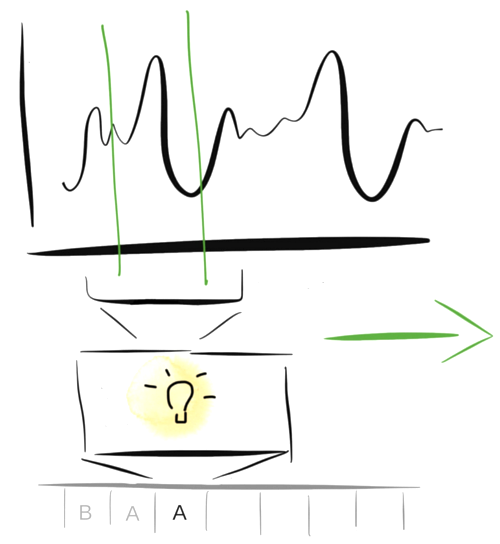

Let’s start understanding what the system we will implement will do. We can think of the system as having three sequential components:

- Preprocessing: Segment the audio sequence by sliding a small window across time.

- Model: Recognize the note that constitutes each segment.

- Postprocessing: Combine the note outputs over all of the windows to get the melody.

Taking sliding time windows over the audio, a model identifies the presence of single notes in each of the segments, the outputs of which are postprocessed to get the melody.

Taking sliding time windows over the audio, a model identifies the presence of single notes in each of the segments, the outputs of which are postprocessed to get the melody.

The preprocessing step is straightforward: one simply needs to do is find a window size large enough that it can contain the entirety of one note, but small enough so it doesn’t contain two notes. In the domain object detection, where different objects can be of different scales, it is common to find sliding windows of multiple scales being used. However, in this application, we can get away with setting a constant window size, because the notes are of the same length.

The model and postprocessing step, then, are the meat of the difficulty. The model is responsible for recognizing the note that constitutes each segment, and the postprocessing for combining the outputs of the model to infer the underlying melody.

A Model for Recognizing Notes in Audio Segments

Our model will take a segment of audio as input and determine which note, if any, was played in that segment. One way to formulate this task is as a multiclass classification problem with $ n + 1 $ classes, where the extra note class denotes silence or background noise. An alternative, often seen in character recognition, is to break the task into detection and recognition steps such that a detector decides whether or not a segment contains a note and a recognizer then classifying the positive detected note into one of $n$ classes. In our experiments, we found that posing the task as an $ n + 1 $ class classification worked better.

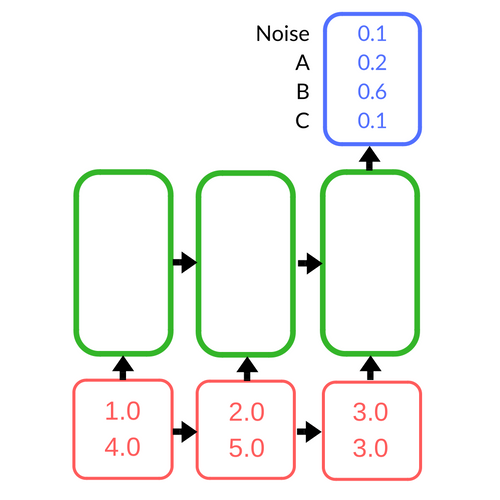

We haven’t yet defined what an audio segment is. We can think of an audio segment as a sequence of samples $[s_1, s_2, … s_t]$, where each sample is a two-dimensional real-valued vector $[ v_l , v_r ]$. Here, the values represent the instantaneous amplitude of the audio signal in the left and right audio channels. For the purposes of our example, let’s use the following length-3 sample input: $x = [ [1.0, 4.0] , [2.0, 5.0], [3.0, 3.0] ] $. Our model maps this input to a probability distribution over all the possible notes. If the possible outputs were A, B, C (and the noise class), then a sample output might look like $ y = [noise: 0.1, A: 0.2, B: 0.6, C: 0.1]$.

Recurrent Neural Networks to Model Temporal Dependencies

The temporal properties of audio make it inherently sequential. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) are a special class of neural networks that can exploit this sequential structure, using information from the past to guide decision making in the present.

The recurrent network takes in a sample at each time step as input (red), and at the last time step, produces a probability distribution over the possible notes as output (blue). In the hidden (green) layer, the network is propagating information through timesteps.

The recurrent network takes in a sample at each time step as input (red), and at the last time step, produces a probability distribution over the possible notes as output (blue). In the hidden (green) layer, the network is propagating information through timesteps.

(See Alex Graves’ thesis and Andrej Karpathy’s post for some really cool RNN work)

To an RNN, we feed in the input one audio sample at a time until we’ve exhausted all of the samples in the audio segment. Typically, when one uses an RNN network, the specific variant of recurrent network used is an LSTM, which is better at handling longer sequences of input. It is also typical to stack multiple hidden (green) LSTM layers on top of each other to form a deep network, so that each subsequent layer learns a slightly more abstract representation of the data, which turns out to be useful in improving the accuracy of the classification. Once all of the samples in the segment are fed into the network, the network outputs scores for each note, which are normalized to translate to probabilities for each class – how likely it was that any of the notes were played in that specific segment.

We thus train an RNN on several hours of synthetically generated audio data. One effective trick used for training the network, also commonly seen in speech recognition, is to mix different kinds of noise on the clean audio data. With this, we are not only able to augment the size of the dataset, but also make the network more robust to noisy audio environmments.

Postprocessing Sliding Window Outputs To Label Sequences

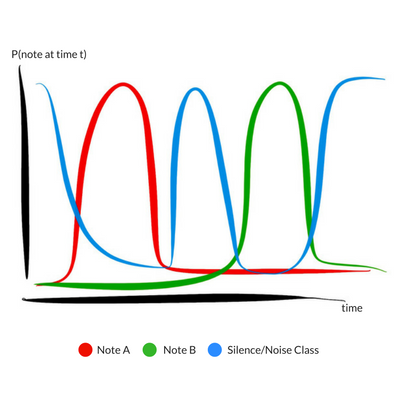

The model described above is trained to output a probability distribution over the possible classes for each segment of the sliding window. The final step is to combine the outputs of each of these segments to get the melody.

Sliding window outputs over time show changing probabilities of classes across time.

Sliding window outputs over time show changing probabilities of classes across time.

![Non-Maximum Suppression keeps the local maxima, which can be used to recover the underlying melody [Note A, Note B] Non-Maximum Suppression keeps the local maxima, which can be used to recover the underlying melody [Note A, Note B]](/mlx/recognizing-musical-melodies/post-nms.png) Non-Maximum Suppression keeps the local maxima, which can be used to recover the underlying melody [Note A, Note B]

Non-Maximum Suppression keeps the local maxima, which can be used to recover the underlying melody [Note A, Note B]

To recover the underlying melody from sliding window outputs, we use a variant of Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS). The basic idea of NMS is to look at each point in the sequence, and suppress neighbouring points that are smaller to zero. At the end of the NMS run, only the local maxima remain. Maxima separated by the silence / noise class can then be read off as the notes constituting the melody.

In Summary

We have described a simple machine learning approach to recognize musical melodies with a concrete application in secure audio pairing. For the learning system, we use a sliding window to break a large chunk of audio into smaller segments, run a Recurrent Neural Network – which captures temporal properties of audio – over each of those segments to make segment-level predictions, and finally use Non-Maximum Suppression to postprocess the outputs. This system is a part of a security protocol which involves devices establishing a secure connection with each other by playing a short audio sequence, which the other device must recognize.

This is work done at Stanford University, advised by Professor Dan Boneh