Question answering is an important NLP task and longstanding milestone for artificial intelligence systems. QA systems allow a user to ask a question in natural language, and receive the answer to their question quickly and succinctly. Today, QA systems are used in search engines and in phone conversational interfaces, and are pretty good at answering simple factoid questions. But on more complex questions, these usually only go so far as to return a list of snippets that we the users then have to browse through to have our question answered.

The ability to read a piece of text and then answer questions about it is called reading comprehension. Reading comprehension is challenging for machines, requiring both understanding of natural language and knowledge about the world.

How can we get a machine to make progress on the challenging task of reading comprehension? Historically, large, realistic datasets have played a critical role in driving fields forward – one famous example is ImageNet for visual recognition.

In reading comprehension, we mainly find two kinds of datasets: those that are automatically generated, and those that are manually generated. The automatically generated datasets are cloze style, where the task is to fill in a missing word or entity, and is a clever way to generate datasets that test reading skills. The manually generated datasets follow a setup that is closer to the end goal of question answering, and other downstream QA applications. However, these manually generated datasets are usually small, and insufficient in scale for data intensive deep learning methods.

To address the need for a large and high-quality reading comprehension dataset, we introduce the Stanford Question Answering Dataset, also known as SQuAD. At 100,000 question-answer pairs, it is almost two orders of magnitude larger than previous manually labeled reading comprehension datasets such as MCTest.

The SQuAD setting

The reading passages in SQuAD are from high-quality wikipedia articles, and cover a diverse range of topics across a variety of domains, from music celebrities to abstract concepts. A passage is a paragraph from an article, and is variable in length. Each passage in SQuAD has accompanying reading comprehension questions. These questions are based on the content of the passage and can be answered by reading through the passage. Finally, for each question, we have one or more answers.

One defining characteristic of SQuAD is that the answers to all of the questions are

segments of text, or spans, in the passage. These can be single or multiple words, and are not limited to entities – any span is fair game.

Answers are spans in the passage

Answers are spans in the passage

This is quite a flexible setup, and we find that a diverse range of questions can be asked in the span setting. Rather than having a list of answer choices for each question, systems must select the answer from all possible spans in the passage, thus needing to cope with a fairly large number of candidates. Spans comes with the added bonus that they are easy to evaluate.

In addition, the span-based QA setting is quite natural. For many user questions into search engines, open-domain QA systems are often able to find the right documents that contain the answer. The challenge is the last step of “answer extraction”, which is to find the shortest segment of text in the passage or document that answers the question.

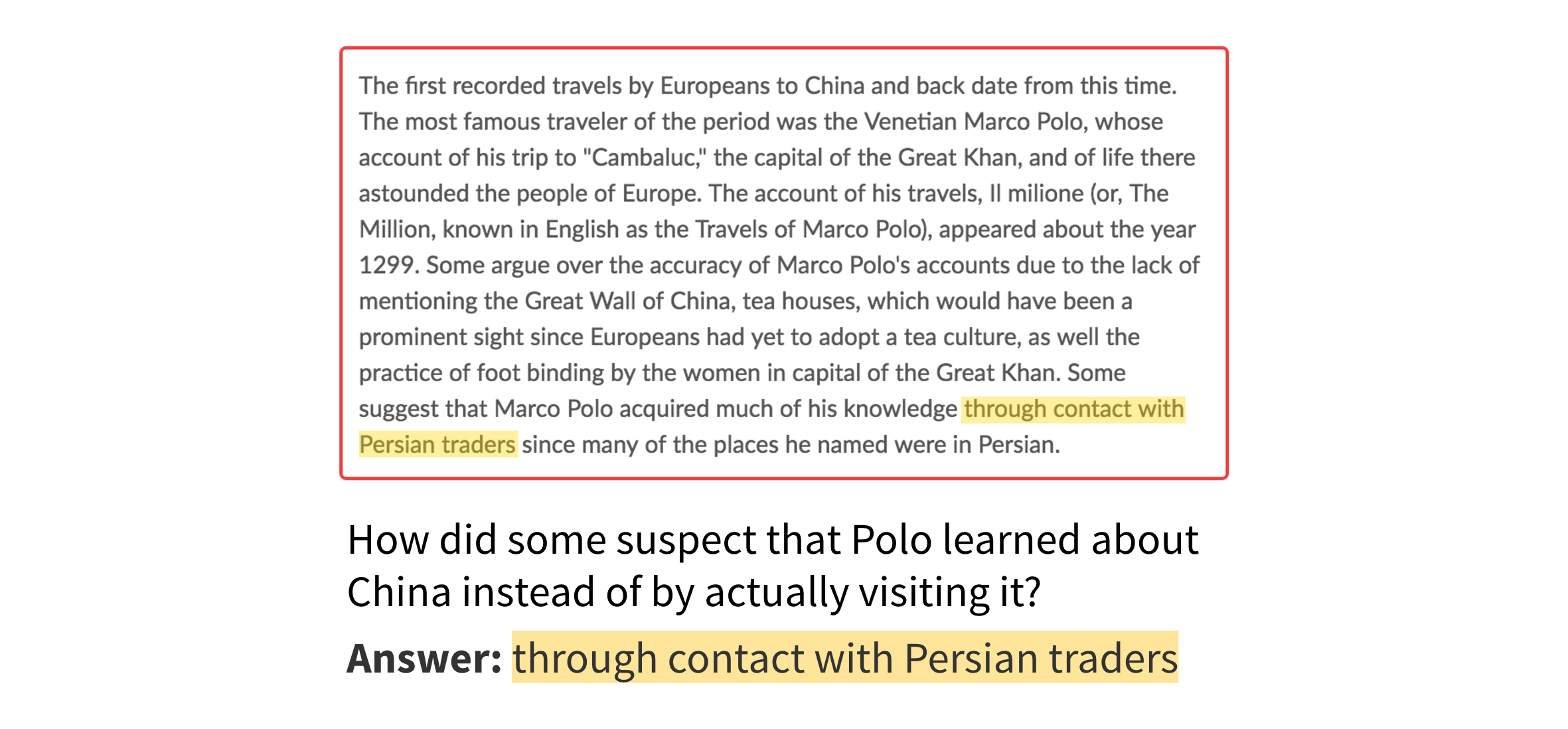

Before we dive into the dataset, let’s understand the data collection process. SQuAD is a large crowdsourced effort. On each paragraph, crowdworkers were tasked with asking and answering several questions on the content of that passage. The questions had to be entered in a text field, and the answers highlighted in the passage. To guide the workers, we had examples of good and bad questions. Finally, crowdworkers were encouraged to ask questions in their own words, without copying word phrases from the passage. The result – a more challenging dataset, where simple string matching techniques will often fail to find correspondences between passage words and question words.

SQuAD Data Collection Interface

SQuAD Data Collection Interface

A taste of challenges in SQuAD

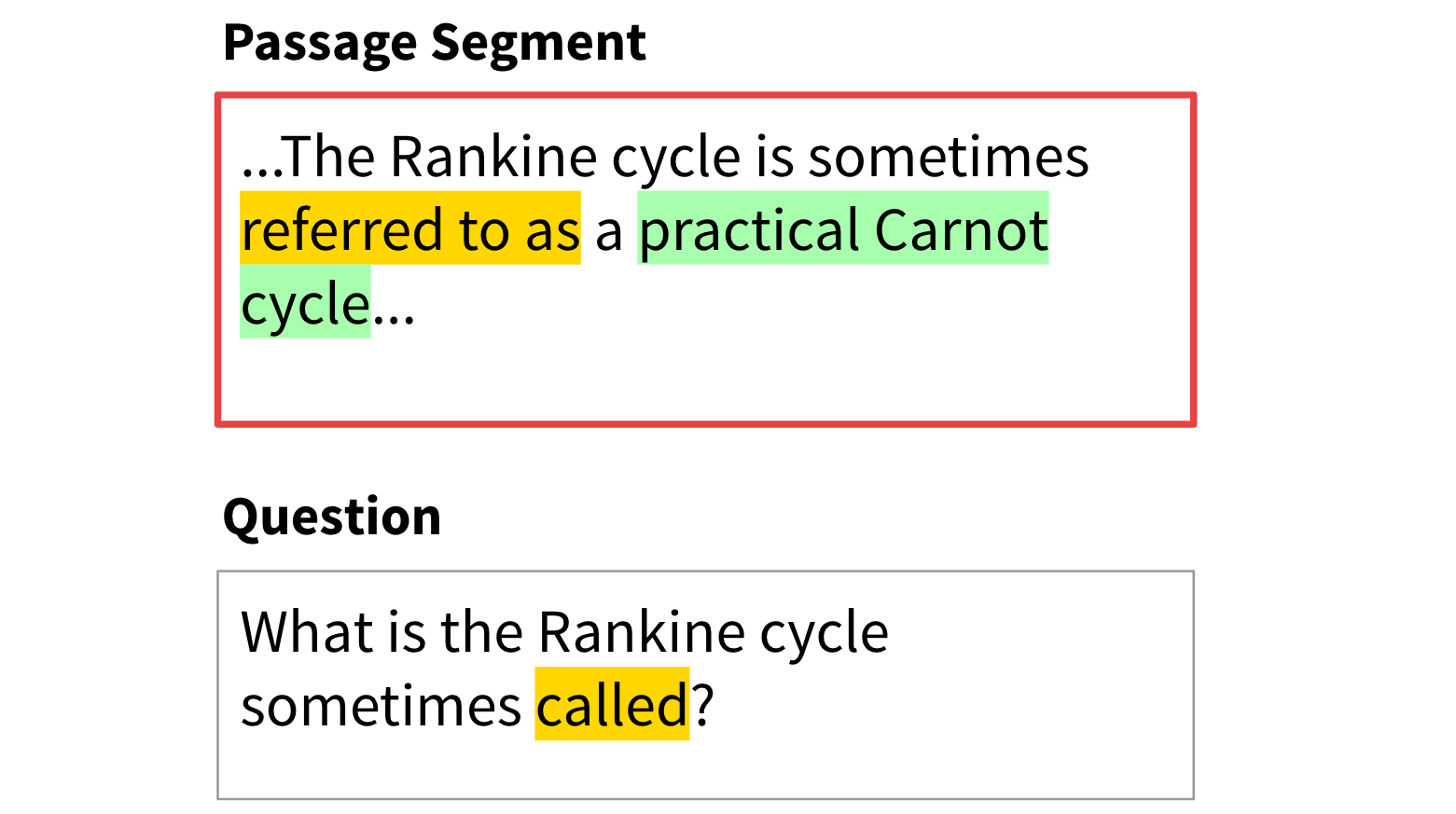

Because crowdworkers are asked to pose questions in their own words, question words are often synonyms of words in the passage – this is lexical variation because of synonymy. In a few hundred examples that we manually annotated, this case was fairly frequent, necessary in about 33% of questions.

In this example, a QA system would have to recognize that “referred” and “call” mean the same thing.

In this example, a QA system would have to recognize that “referred” and “call” mean the same thing.

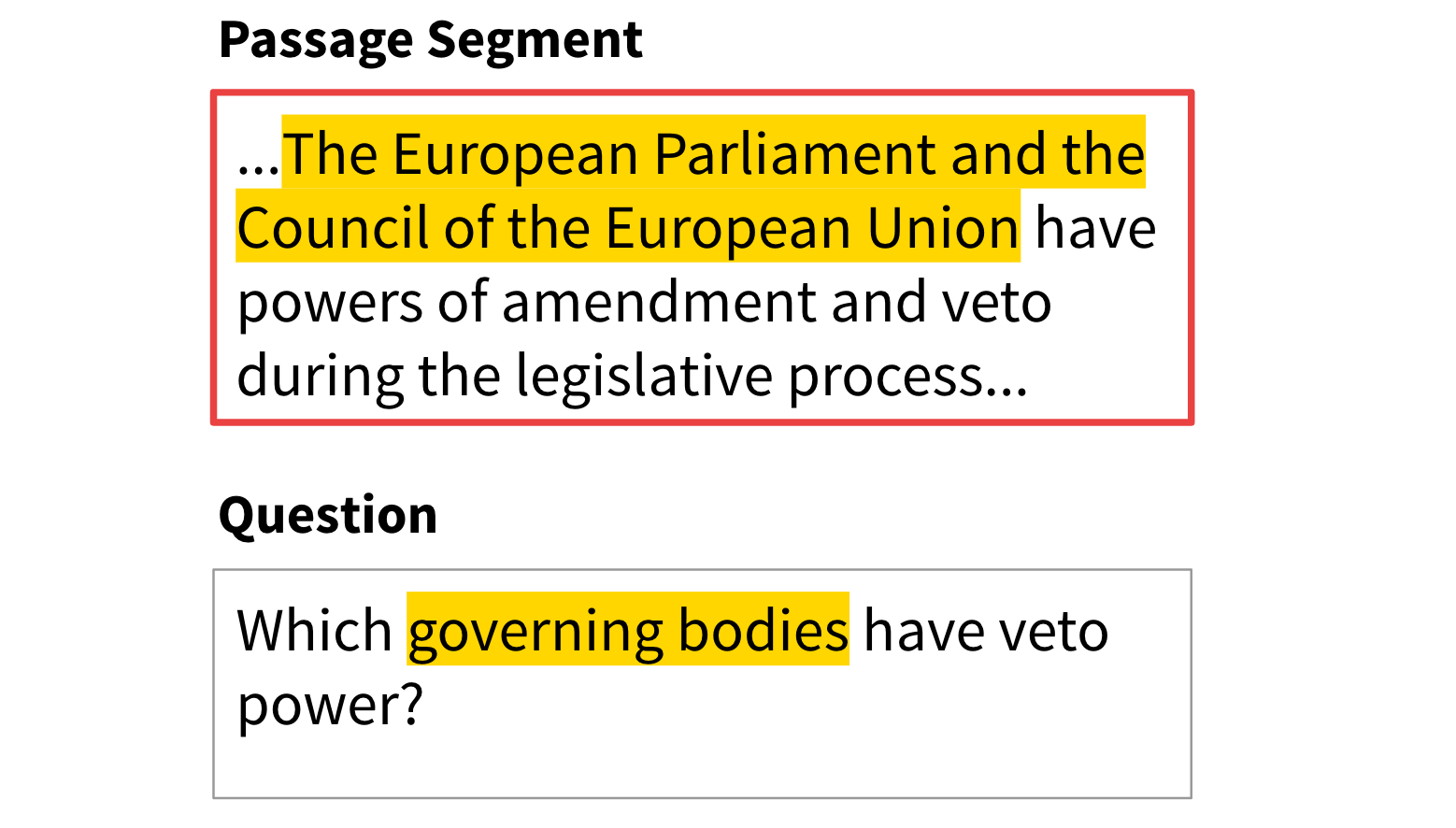

The second type of reasoning we look at is lexical variation that needs external knowledge to reason about.

To answer this question, QA systems have to infer that the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union are government bodies. Such questions are difficult to answer because they go beyond the passage.

To answer this question, QA systems have to infer that the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union are government bodies. Such questions are difficult to answer because they go beyond the passage.

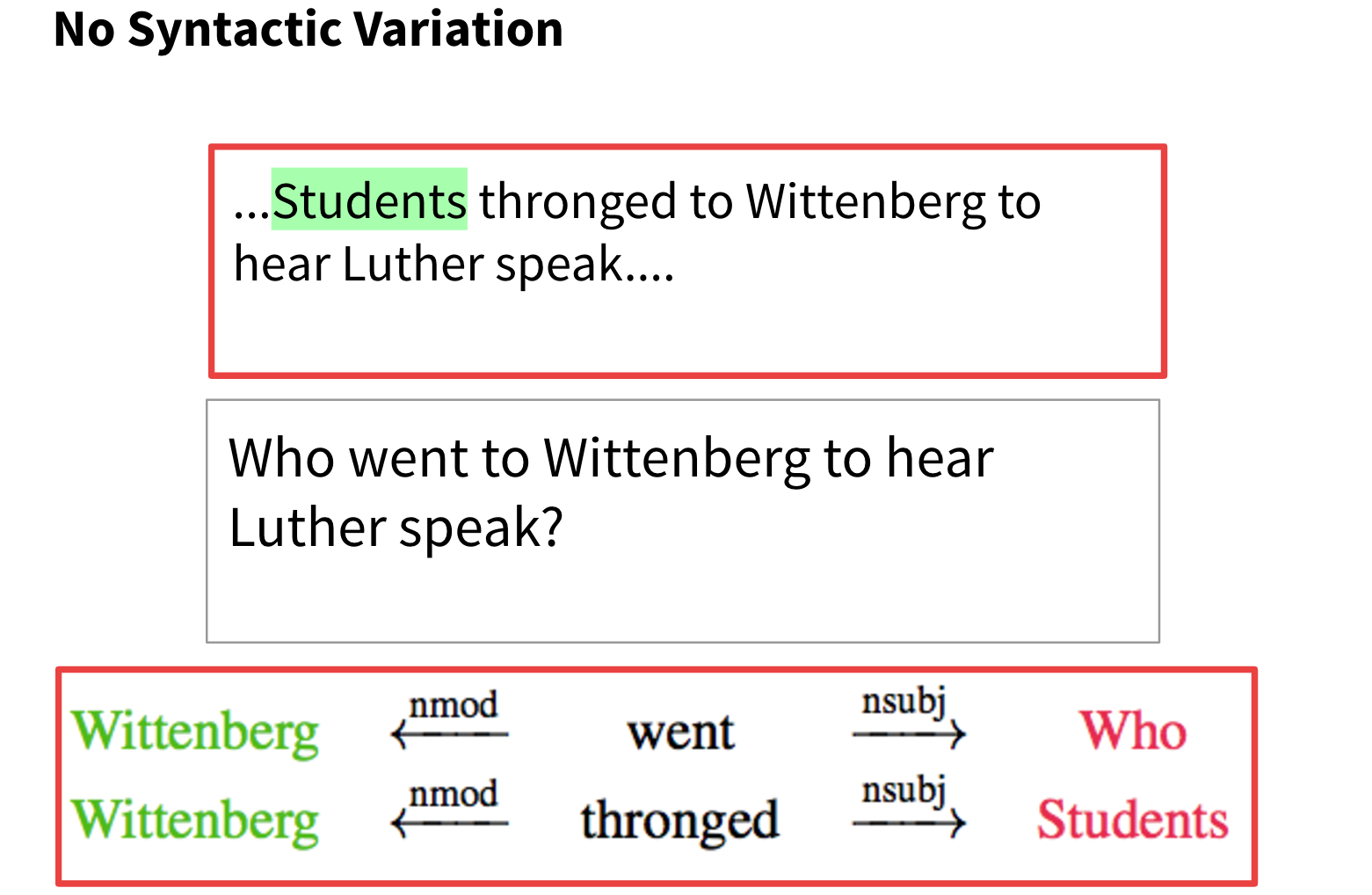

Other than lexical variation, we also have syntactic variation, which compares the syntactic structure of the question with the syntactic structure of the passage.

Here’s a question which does not require handling of syntactic variation. The question and the passage have matching syntactic structures ‘who went to wittenberg’, ‘students thronged to wittenberg’ even though the the question uses the word ‘went’ and the passage uses the word ‘thronged’. Questions without syntactic variation are relatively easy to answer because the syntactic structure gives all of the information needed to answer it.

Here’s a question which does not require handling of syntactic variation. The question and the passage have matching syntactic structures ‘who went to wittenberg’, ‘students thronged to wittenberg’ even though the the question uses the word ‘went’ and the passage uses the word ‘thronged’. Questions without syntactic variation are relatively easy to answer because the syntactic structure gives all of the information needed to answer it.

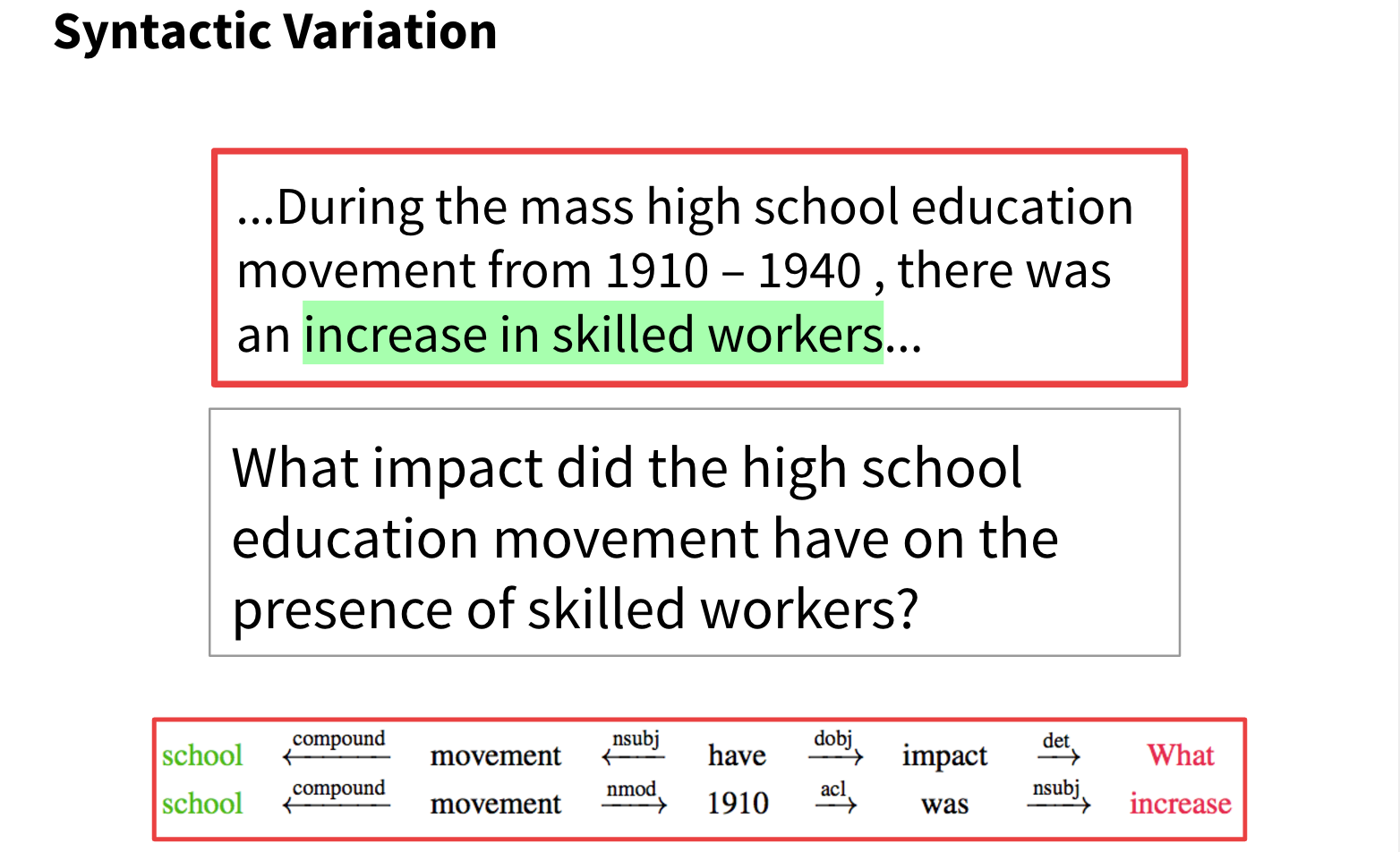

Here is a case which does exhibit syntactic variation. Comparing the parse trees of the question and the sentence in the passage, we find that their structure is fairly different. Reasoning about syntactic variation is required very frequently, necessary in over 60% of the questions that we annotated.

Here is a case which does exhibit syntactic variation. Comparing the parse trees of the question and the sentence in the passage, we find that their structure is fairly different. Reasoning about syntactic variation is required very frequently, necessary in over 60% of the questions that we annotated.

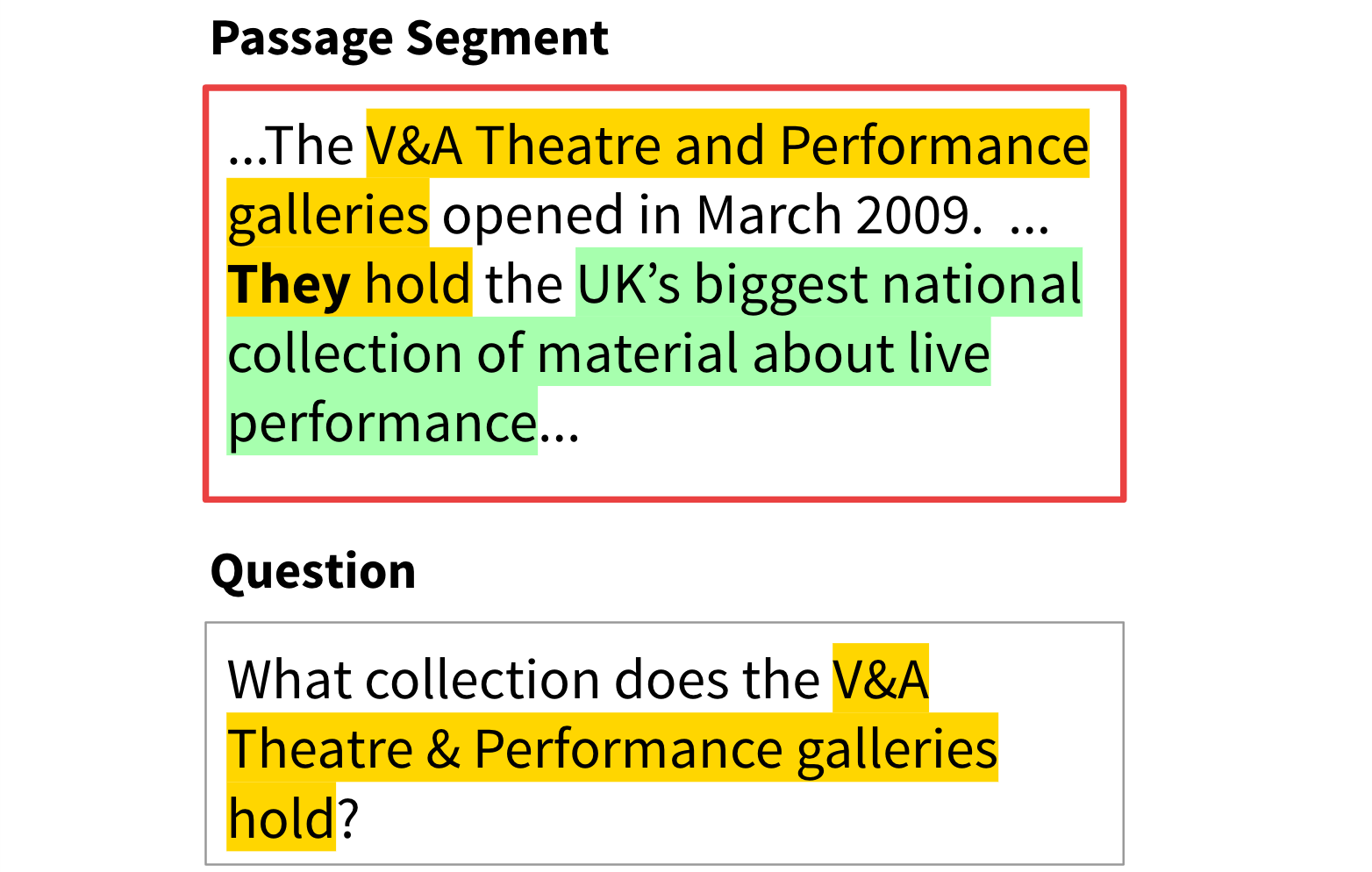

Finally there is multi-sentence reasoning. For these kind of questions, we need to use multiple sentences in the passage to answer them. Much of the time, this involves conference resolution to identify the entity that a pronoun refers to.

An example case that requires multi-sentence reasoning.

An example case that requires multi-sentence reasoning.

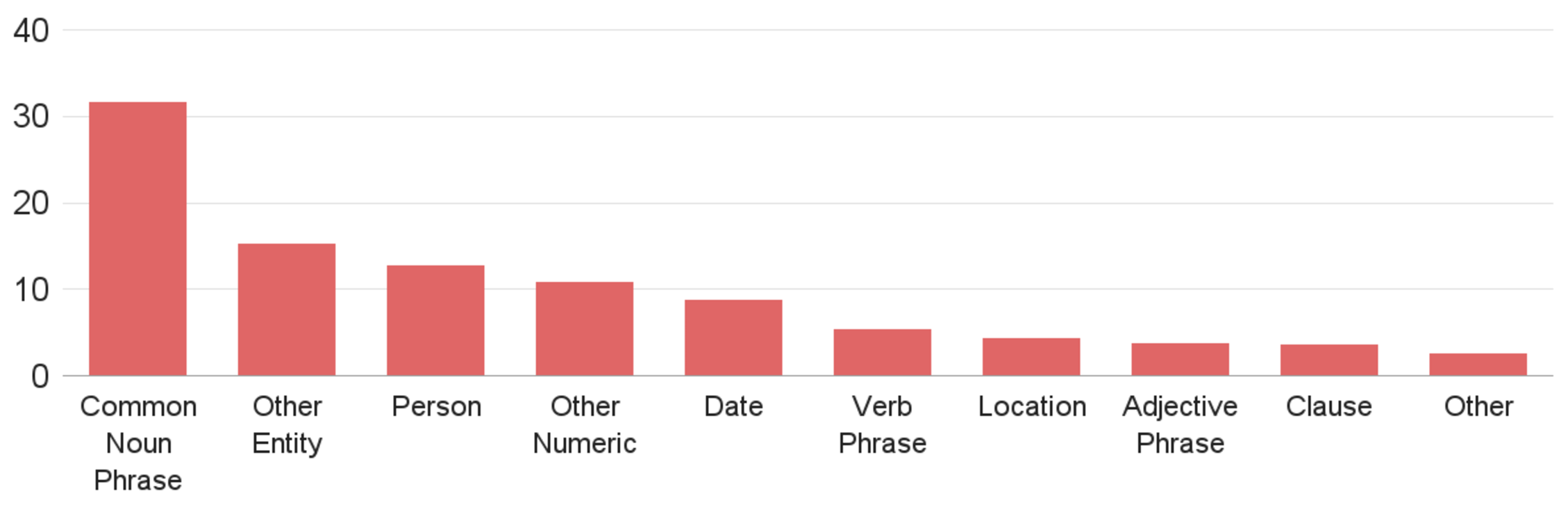

Now that we’ve looked at the diversity of questions in SQuAD, let’s look at the diversity of answers in the dataset. Many QA systems exploit the expected answer type when answering a question. For instance, if there is a ‘how many’ question, a QA system might only consider answer candidates which are numbers. In SQuAD, answer types in SQuAD are wide-ranging, and often include non-entities and long phrases. This makes SQuAD more challenging and more diverse than datasets where answers are restricted to be of a certain type.

Diversity of Answer Types.

Diversity of Answer Types.

SQuAD models and results

SQuAD uses two different metrics to evaluate how well a system does on the benchmark. The Exact Match metric measures the percentage of predictions that match any one of the ground truth answers exactly. The F1 score metric is a looser metric measures the average overlap between the prediction and ground truth answer.

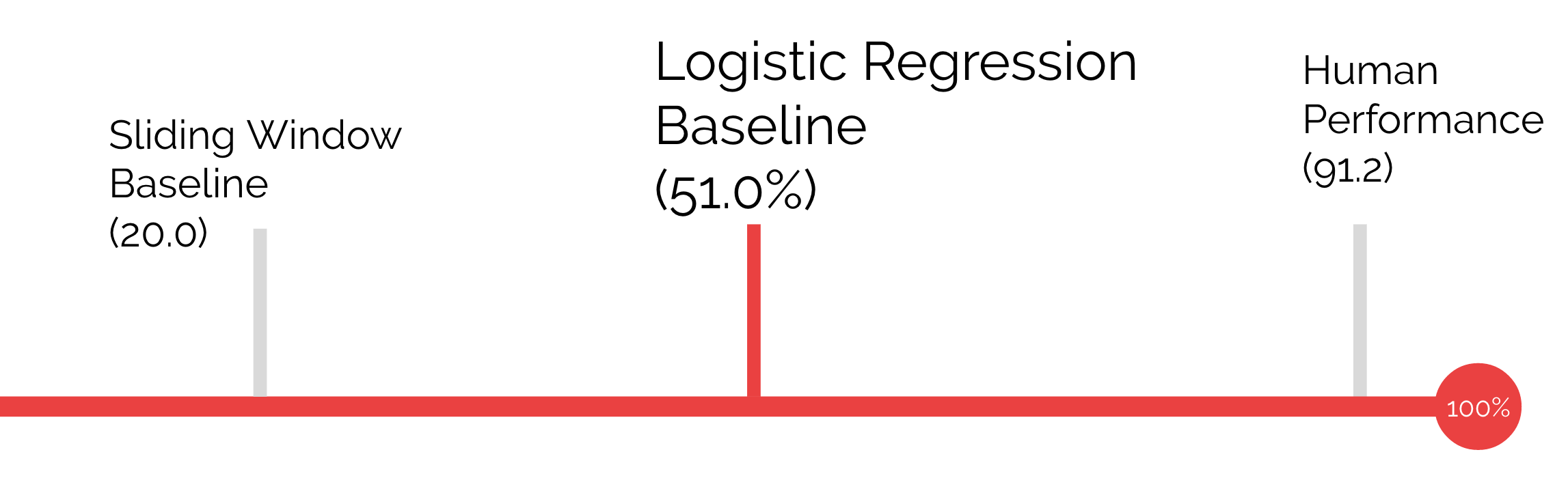

We first assess human performance on SQuAD. To evaluate human performance, we treat the one of the crowdsourced answers as the human prediction, and keep the other answers as ground truth answers. The resulting human performance score on the test set is 82.3% for the exact match metric, and 91.2% F1.

Human Performance

Human Performance

To compare the performance of machines with the performance of humans, we implemented a few baselines. Our first baseline is a sliding window baseline, in we extract a large number of possible answer candidates from the passage, and then match a bag of words constructed from the question and candidate answer to the text to rank them. Using this baseline, we get an F1 score of 20.

Compared with human performance on SQuAD, machines seem like a really long way with this baseline. But we haven’t yet incorporated any learning into our system. And we expect with a large dataset, learning can do well.

To improve upon the sliding window baseline, we implemented a logistic regression baseline that scores candidate answers. The logistic regression uses a range of features – let’s touch on the features we found to be most important, namely the lexicalized features, and dependency tree path features.

Let’s first look at lexicalized features.

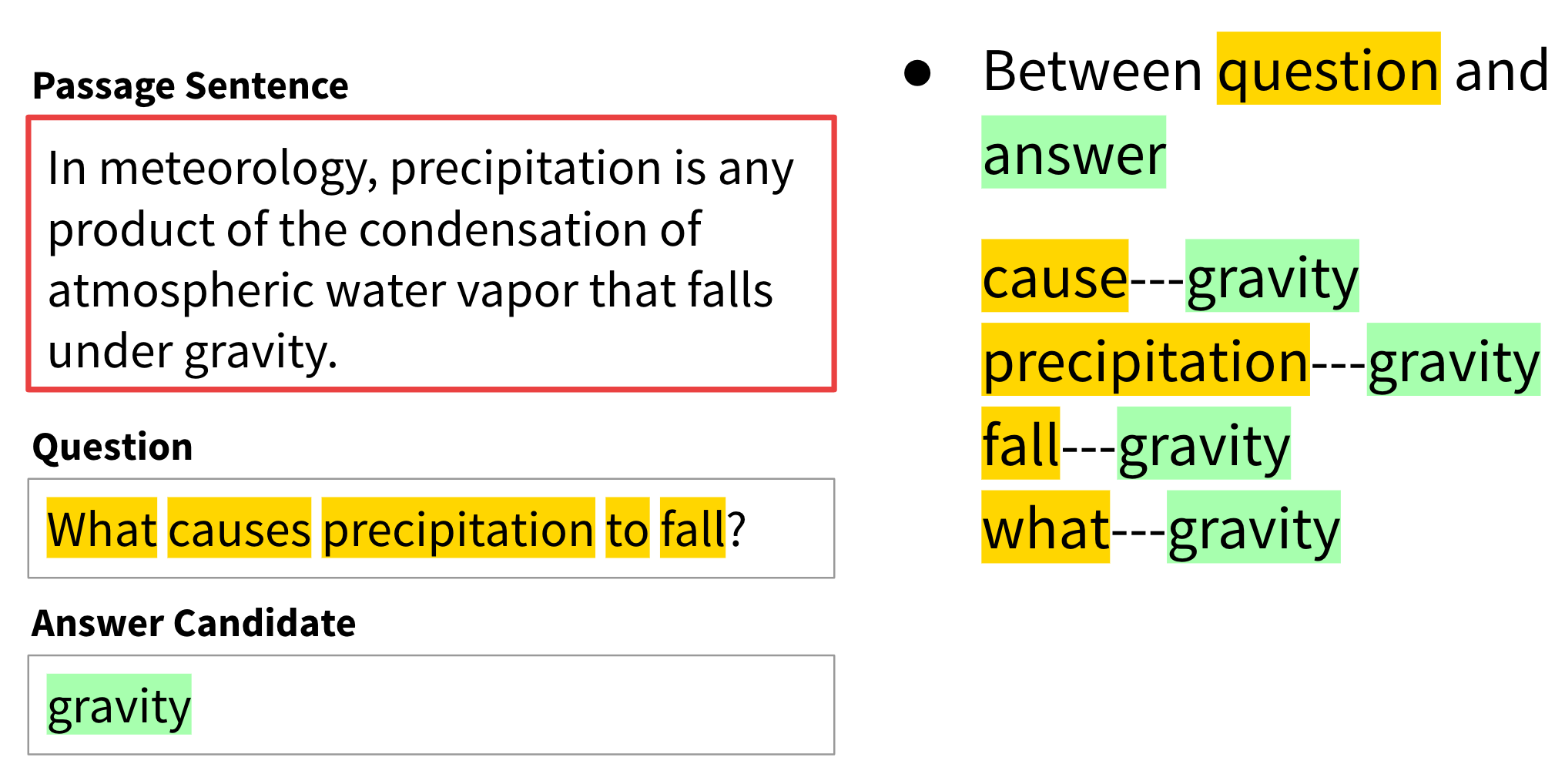

Question word lemmas are combined with answer word lemmas to form pairs like these.

Question word lemmas are combined with answer word lemmas to form pairs like these.

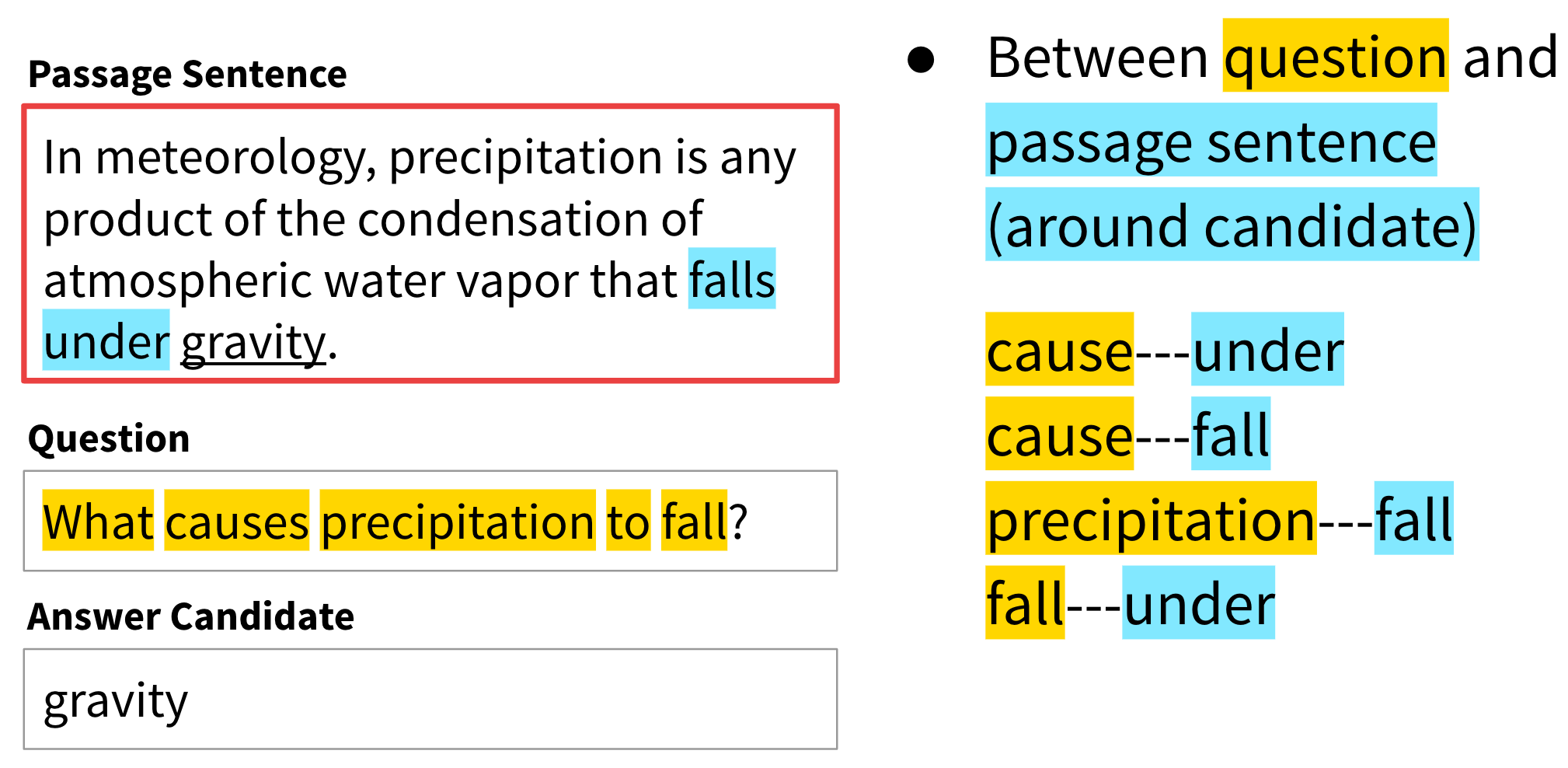

We also combine question words with passage sentence words that are close to the answer.

We also combine question words with passage sentence words that are close to the answer.

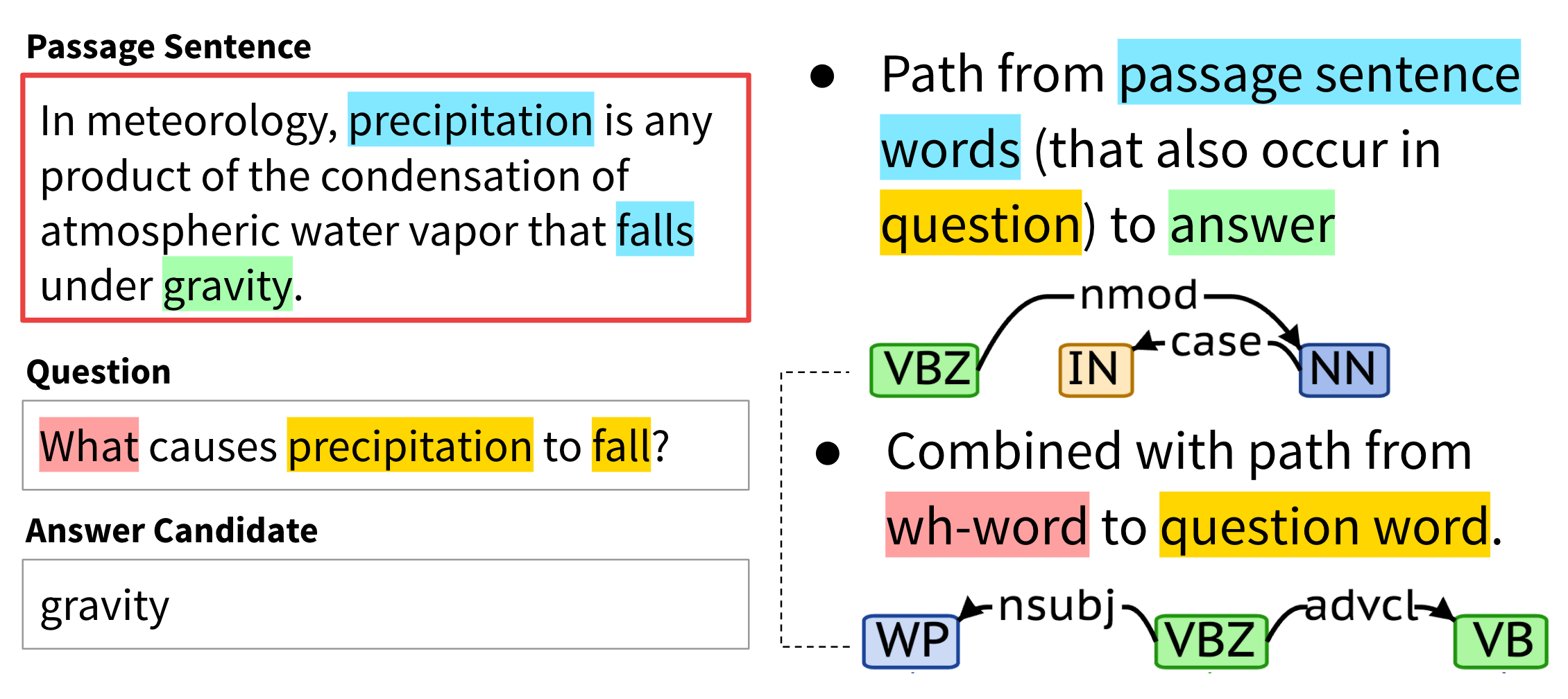

Next, let’s look at dependency features. We use the dependency tree path from the passage sentence words that occur in the question to the answer in the passage. This is optionally combined with the path from the wh-word to the same question word.

We use the dependency tree path from the passage sentence words that occur in the question to the answer in the passage. This is optionally combined with the path from the wh-word to the same question word.

Using these features, we build a logistic regression model which sits between the sliding window baseline and human performance. We note that the model is able to select the sentence containing the answer correctly with 79.3% accuracy; hence, the bulk of the difficulty lies in finding the exact span within the sentence.

Comparing Performances

Comparing Performances

Reading comprehension is a challenging task for machines. Comprehension refers to the ability to go beyond words, to understand the ideas and relationships between ideas conveyed in a text. The TREC paper, written at the start of the millennium, that introduced one of the early QA benchmarks, opens by mentioning that a successful evaluation requires a task that is neither too easy nor too difficult for the current technology. If the task is simple, all systems do well and nothing is learned. Similarly, if the task is too difficult, all systems do poorly and again nothing is learned.

Since our paper came out in July 2016, we have witnessed significant improvements from deep learning models, and have had many submissions compete to get state of the art results. We expect that the remaining gap will be harder to close, but that such efforts will result in significant advances in machine comprehension of text.

You can check out the leaderboard, explore the dataset and visualize model predictions. All of the data and experiments are on Codalab, which we use for official evaluation of models.